False Facts in Last Seen Podcast Episode 3

1. LEPPO: ”This was a well-organized, a

well-organized thing. The proof is in the pudding. They haven’t found a thing.”

HORAN: “By “they,” Leppo means

the FBI. And he’s right. In the 28-and-a-half years since the heist, they haven’t

found any of the stolen masterpieces.”

Martin Leppo didn't say stolen masterpieces. He said, “a

thing.” He is a defense attorney, and there is every reason to believe that is

what he meant. The fact is “they haven’t found a thing: since the FBI took

exclusive control of the investigation on the first day. The have found zero evidence

from at least seven crime scenes on three floors of the Gardner Museum.

2. AMORE: “And Merlino would be at Walpole

and he would have the most desirable cell. He would be in really well with the

prison leadership because he was likable and people listened to him. And I

don't want to say it's like that scene in "Goodfellas" where they go

to jail and it's a big party and people are cutting up garlic for their pasta

sauce, but Merlino made the best of it.“

Merlino

went to prison for being a lookout on an armored car heist in the North End shortly

after Christmas, on December 28 1968, twenty years before the Gardner heist. Even after he

had been out for ten years, he was not a Mafia don, or even a member of the Mafia.

He was kind of a little bit on the [Mafia] wannabe side, according to Ulrich

Boser, author of “The Gardner heist.”

3. RODOLICO: “The painting he dangled

wasn’t a Rembrandt slashed from its frame at the Gardner Museum.”

There

were no Rembrandts slashed from their frames in the Gardner heist, there were

two Rembrandts “neatly cut” from their stretchers.

False Facts in Last Seen Podcast Episode 4

1. BOSER: “My name is Ulrich Boser, and I'm

the author of "The Gardner Heist." My book argued that David Turner

and George Reissfelder were the individuals who robbed the museum.”

To

say that his book “argued” Turner and Reissfelder were the thieves is quite an

overstatement: “If Turner was involved,

George Reissfelder was probably his main accomplice, the shorter thief.” Boser’s wrot in his book, "The Gardner Heist," on page 199.

Somehow book reviewers missed what Boser claims is this

essential point of his book. None I found online referenced Turner or

Reissfelder. Publisher’s Weekly wrote: “After the death of a legendary

independent fine arts claims adjuster, Harold Smith, who was haunted by the

Gardner robbery. Boser carried on Smith’s work, pursuing leads as varied as

James “Whitey” Bulger’s Boston mob and the IRA.”

And

around the same time in 2018 Boser said on a different podcast Empty Frames

that "I'm less certain about that we know the two individuals who walked

in as much as we have that clustering, whether

its Leonardo DiMuzio, George Reissfelder, David Turner you've got the

crewish we feel good about. Boser's book perhaps insinuates it was Reissfelder and Turner. Argues implies that Boser provided evidence of their involvement. He does not.

2. MURPHY: “[In 2016] "I was hearing some

things about whether or not he might cooperate. And I looked at the Bureau of

Prisons’ website, which shows a release date. And when I looked at it, I knew.

I said that wasn’t the release date that was there before. And I noticed that

the release date had changed. So that’s how I saw it, that I knew that he

initially was supposed to get out on one date. And suddenly, they just took off

a bunch of years.”

HORAN: “David Turner’s 38-and-a-half-year

prison sentence was suddenly seven years shorter. Why?”

It was not suddenly seven years shorter. The Boston Globe had twice reported three

years prior, in 2013, that Turner was scheduled to get out in 2025 without

remark, including one story that had a Shelley Murphy byline.

There is no proof that Turner received a secret

sentence reduction. The release date shown on the BOP website does not indicate or

suggest a reduced sentence since the BOP.gov website which serves as the sole source

for the Boston Globe’s secret sentence reduction story, states specifically,

that: “the projected release date displayed reflects the inmate's statutory

release date (expiration full term minus good conduct time)” and not the full sentence

the person received from the judge.” https://www.bop.gov/inmateloc/about_records.jsp

If Robert Gentile, for example served his full

sentence he would have gotten out in 2020, not 2019, but the BOP.gov website

very closely matched Gentile’s actual release date and not the sentence he received

from a judge.

One of David Turner’s partners in the Loomis armored

car depot sting was Stephen Rossetti, who received a sentence six years

longer than David Turner for involvement

in the same crime and Rossetti was released from prison shortly before

Turner.

In May of this year, Murphy reported that Relatives of federal prisoner Fotios “Freddy” Geas, Paul J. DeCologero, and Sean McKinnon, say they are being denied “basic human rights” in the Special Housing Unit at US Penitentiary Hazelton. The article further states that McKinnon received and eight year sentence and will be out in 2002. McKinnon received an eight year sentence, and the BOP.GOV website does indeed show him getting out in 2022, but he was given that sentence in 2016, so by the Boston Globe formula the bop.gov should be showing McKinnon getting out in 2024, not 2022.

Also Paul J. DeCologero, in the same story, Murphy reported DeCologero has "has five years left on a 25-year sentence," that would have him getting out in 2026. Except DeCologero was sentenced to 25 years in 2006, so by the Boston Globe formula the bop.gov website should show DeColegero getting out in 2031, in ten years, not five.

Are McKinnon and DeCologero, like David Turner, recipients of a secret sentence reductions also?

How about Devontay Douglas? In July of this year, six weeks ago as I write this, Douglas was sentenced to ten years for carjacking, and yet the bop.gov website shows him getting out in 2027, not 2031. I did over a dozen searches on the justice.gov and the dea.gov websites, and matched their press releases up with the bop.gov website, and I not find a single instance where the BOP.GOV release date matched the sentence received by the inmate. The site always shows a shorter periode, reflecting the bop.gov's stated policy, of showing a "statutory release date, not the full sentence."

And even if Turner had received a sentence reduction there is no evidence, or indication that it was in any way related to the Gardner heist. This shows the desperation of investigators to tie David Turner to the Gardner heist, someone who received harsh consequences for his misdeeds at the hands of federal authorities.

3. MURPHY: “It's

frustrafting. All these theories are frustrating. For everything that points

toward these particular suspects there's something that points away.”

If there is as much exculpatory evidence,

evidence, that points away as there is evidence pointing to the suspects, which

is very little, then these are public relations place holders, not actual suspects.

4. HORAN: “And after

that? There are no credit card receipts for the day of the heist, March 18.

But, Steve says, there is one for two days after — March 20.”

KURKJIAN: “It showed he was turning in a

vehicle, a rental car, at the Fort Lauderdale airport, and using his credit card

to pay for that vehicle. But on that receipt is another driver’s license

number.“

KURKJIAN: “This was a ploy

by him in order to later tell the investigators, “Oh, I was in Florida at the

time.”

HORAN: “It’s-- he created

an alibi.”

KURKJIAN: “He created an alibi.”

Awkward wording about this piece of evidence (“Steve

says” “it showed) return of a rental car in Fort Lauderdale well over 48 hours

after the Gardner heist in Boston is not an alibi. Therefore, Turner didn’t “create

an alibi.”

5. HORAN: “In 1974, the

pair [Reissfelder and Beauchamp] escaped from prison.”

Reissfelder

didn’t escape from prison, he simply didn’t return from a one-day furlough

6. BEAUCHAMP: “Turner was

interested in getting out of the drug business. And I kept telling Reissfelder

the same thing.”

There is no corroboration for any of Beauchamp’s

claims and Anthony Amore, for one, has said Beauchamp is not credible: “Every single

person, so far, one them is Myles Connor, one of his associates is Billy

Youngworth, who's come forward and said it, this guy, his name is Robert

Beauchamp, who was the prison lover of a guy named George Reissfelder, who

I was talking about earlier, they're all charlatans and that's the nicest word

I can use for them. Hucksters.

7. HORAN: “Even as that

documentary aired, Santos was trying to find the courage to leave Reissfelder.

She finally managed it in 1989. The following year, her divorce would come through,

and her ex-husband would join a cast of men named in connection to the Isabella

Stewart Gardner Museum robbery.”

Reissfelder was not mentioned as a possible

suspect in 1990 or until over 15 years after the Heist. Reissfelder has never

been named as a suspect. No one has ever been named as a suspect. In 1990 there

is no evidence to suggest investigators were looking for the kind of local suspects

associated with the Gardner Heist for the past ten years. .

Boston Globe 5/14/90 “As details begin to

emerge about the two-month probe, law enforcement sources said that the

suspects' movements are under close scrutiny by federal agents, including one

suspect who was under surveillance during a recent arrival at Logan Airport…

Sources were divided as to whether any of the suspects were currently in

Massachusetts, noting that they frequently traveled from city to city.

The FBI made no attempt to speak with Myles

Connor in 1990, Boston Globe 5/13/90, and never spoke with James “Whitey”

Bulger about the robbery.

Interview of FBI Boston SAIC Richard DesLauriers May 13, 2013

Mike Nikitas: "Whitey Bulger got arrested a year

and a half ago, have you ever talked to him about this, asked him whether he

knows anything about it [the Gardner Heist]?"

SAIC DesLauriers: "No."

Nikitas: "You haven't?"

SAIC DesLauriers: "No."

Nikitas: "And you think it wouldn't be worth

doing that?"

SAIC DesLauriers: "No. There's no connection to

the Bulger investigation."

Nikitas: "Does he, maybe he knew of the theft?"

SAIC DesLauriers: "There's no connection to the

Bulger investigation." Time: 4:03

“As of the time I left (in 2001), they knew no

more than they did the day it happened." —retired

FBI agent and Gardner heist investigation supervisor Tom Cassano

Some months after we met, I called the agent [Retired

Gardner heist FBI investigator Robert Wittman] to check in, and during our

conversation, I asked him about some of the people who’ve been accused of being

behind the heist over the years, people like David Turner and Bobby Donati and

George Reissfelder. “Nope,” he said. “Don’t know them.” 2009 “The Gardner Heist” page 114.

8. RODOLICO: “Anthony

Amore, who is still looking at the TRC gang, isn’t so sure [they were not

involved [in the Gardner Heist].”

AMORE: “They were capable.

You know, if someone mentions to you the Merlino gang, which was a pretty big

gang, out of TRC Dorchester, no one doubted their capability to do any sort of

crime. And they were doing all sorts of crimes. And to say that they could have

pulled off the Gardner? Yeah, they could have done it. Absolutely.”

And in 2018, when Last Seen was still in

production, Anthony Amore was asked if he know who did it, and he replied that

he does know who did it, so Amore is sure whether it was the

TRC gang or not.

Also, in 2017 Amore said "Eventually after

ten years [Fall of 2015] because of certain people I was looking at, that I

feel were involved, and I know Myles knew them. One night I decided it's time

to meet Myles." —Anthony Amore 3/30/17

Myles Connor was not associated with TRC, or Merlino,

or Turner, Reissfelder, or DiMuzio. None of these people or TRC are mentioned

in Myles Connor’s own book, or in any public media account. So if the thieves were

people who knew Myles Connor, to the extent that Anthony Amore would, after over

ten years on the job, make the effort to go out and meet with him, then the thieves are not

from this TRC automotive gang, since Myles Connor and this gang are not

connected. "Through Myles [Connor] you're moving away from mobsters or people who want to be affiliated with mobsters." —Ulrich Boser

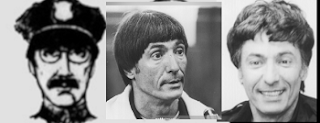

9. HORAN: “George Reissfelder does resemble the police artist’s sketch of one of the suspects. Long narrow face. Prominent chin. Bowl haircut.”

We don’t know what kind of haircut the thieves had from the police sketches. They were wearing police hats. One of the thieves was described as having “puffy black hair.” In any case Reissfelder did not have a bowl haircut in 1990, and while he does have a prominent chin, it is a distinctly squared-off chain that is unlike the police sketch.

10. DESLAURIERS: “For the first time, we can say with a high degree of confidence we've determined that in the years since the theft the art was transported to Connecticut and to the Philadelphia area. For example, recently, we determined that approximately a decade ago some of the art was brought to Philadelphia where it was offered for sale.”

And an FBI press release from

the same day ended with: “where it was offered for sale by those responsible

for the theft.’”

Turner had been incarcerated for 7 years by 2003.

Reissfelder

died in 1991 eliminating the two men as people who could have been to sell the art in Philadelphia at that time, and therefore, "responsible for the theft."

In addition, Abath has said numerous times that

Reissfelder was not one of the thieves. If Abath was not involved, then neither was

Reissfelder. Abath: “I can tell you that George Reissfelder wasn’t one of the guys

in the museum that night. For one thing he was too old (49 at the time of the

robbery). But also, from the pictures

I’ve seen of him he was too swarthy. Unsub #1 was very white, not an albino but

his skin tone was whiter than Reissfelder’s.”

There was nothing hidden in it and the entrance

was not hidden or concealed. It was found with a flashlight from a distance, so

it was a crawlspace, not definitely a hiding space. A hiding place in the “long abandoned house” of a career drug dealer really suggests

nothing in terms of possibly having the stolen Gardner Art. If it was seriously considered a place where

the art might be found, they would have brought in an evidence response team to

look for paint chips or other evidence of the art having been stored there as

they did at the old Suffolk Downs racetrack in 2015.

2. HORAN: There definitely was a hiding place. And

that piqued their interest in Bobby Guarente as a suspect for having at least

possessed the Gardner Museum’s art. On their way out of town, Amore and the FBI

agent stopped off at the home of Bobby Guarente’s widow, Elene.

There are two very different accounts of both what

Elene Guarente told investigators and how it came to be that she spoke to them about

this at all. Two accounts, which would lead someone to come to very different

conclusions about whether or not Elene Guarente’s late husband, Bobby, actually

ever possessed some of the stolen Gardner art.

First, there is Guarente’s own account that was

reported in the Boston Globe, starting in 2012, and in “Master Thieves,” a 2015

book about the Gardner Heist by Last Seen’s consulting producer Stephen

Kurkjian.

And then there is the other, new, Last Seen

podcast version, which was released to the public on October 15, 2018, eight

months after Elene Guarente died. Not only does Guarente not have the opportunity

to give her side of the story, Last Seen does not even acknowledge that

this other separate, contradictory account is part of the public record, even

though it is largely the work of the podcast’s own consulting producer, Stephen

Kurkjian:

Guarente was “adamant” according to Kurkjian, who interviewed

her several times by telephone, “that in

March 2010, the FBI reached out to her, telling Elene that they wanted to talk

to her about the Gardner heist and the missing paintings. She wouldn’t talk.

Instead she reached out to Robert Gentile… ‘Bobby, I’m in need of money,’

she began. ‘I know my husband gave you those stolen paintings. You need to come

to Maine to talk to Earle Berghman. He’s my soul mate. You two need to sort

this out. If you don’t come, I’m calling back the feds.’” [page 144]

And when Gentile refused to come

through for her, “Elene Guarente summoned the FBI’s Geoff Kelly and Anthony

Amore, security chief for the Gardner, to her Maine home and relayed her

suspicions about her late husband, Gentile, and the stolen Gardner paintings. [page 146]

In the Last Seen podcast

version, investigators, whose interest

was piqued by “a hiding place” in an old abandoned farmhouse, decided on their

way out of town to stop by and see Elene Guarente. In Guarente’s own account,

however, she first refused to meet with them but later invited them up to speak

with her.

The Hartford Courant briefly reported

some of this Last Seen podcast version of the story in 2016, with a few differences

in the factual particulars:

“A search by the Gardner

investigators of Guarente's farmhouse turned up empty. But they got a break

when they returned the keys to his widow, Elene Guarente. She declined to

discuss the encounter with The Courant. But a person with knowledge of the

event gave the following account: After first denying even being aware of the

Gardner museum, she blurted out, inexplicably, ‘My Bobby had two of the

paintings.’"

In September of 2017 the Courant

reported that : “Elene Guarente's spontaneous statement early in 2010

invigorated the investigation and brought its weight down on Gentile.”

Elene Guarente shared her version of what happened on the public

record, but there was only “a person with knowledge of the event,” who offered

a contradicting account of what happened in Guarente’s meeting with investigators in her home in

Maine. And that appeared in a

Connecticut newspaper 300 miles away. It was not until after Guarente died,

nine years after the meeting in question occurred and six years after Elene

Guarente had herself gone public with her version of the events that

In determining the truth of the matter, a lot

hinges on the question of whether or not Elene Guarente did indeed speak “spontaneously,”

If her revelation was not “blurted out” as “someone with knowledge claims,” there is more reason to question her

sincerity and credibility.

If Guarente did not actually see the art, as

she told Kurkjian, then it might be as Gentile

said, just talk. Another possibility is

that Guarente and or Robert Gentile were at some point approached to serve as go

bet

weens, but they never actually possessed or

controlled the art. Perhaps they were leery

about how to go about it after what had happened to William Youngworth and

Carmello Merlino in their publicized attempts to make a deal for the return of

the stolen paintings and subsequent ruin.

3. AMORE: She told us a story about when Bobby

got out of jail for the last time that they went to Portland, Maine. And met

with a friend of Bobby’s and his wife and they had dinner at a Howard Johnson’s

up there.

It

was lunch, not dinner, according to two people who were there, Robert Gentile and Elene Guarente, and twin lobsters

were on the menu, which certainly rules out Howard Johnson, a sit-down

hamburger and fries chain, slowly forced out of business by the tsunami of fast

food restaurants opening in the sixties and seventies. Anyone over sixty, who

grew up in New England knows how laughable it is to suggest that Robert “The

Cook” Gentile, who “considers himself a gourmet,” according to the Hartford, CT,

would eat at HoJo’s after a four-hour

drive.

“It

was nothing then for the couple to jump into a car and cross New England for a

meal, according to the” Hartford Courant. But as the creatives in the fictional advertising

agency Sterling Cooper observed about Howard Johnson’s on the Netflix Series, Mad Men, “it's

not a destination, it's on the way to someplace.”

Throwing

in the name of what was once the largest restaurant chain in America, Howard

Johnson’s, may hold the listener’s interest better than, “nobody quite

remembers the name of the restaurant but…” And “dinner” is better than lunch,

since a lunch means they the gangsters exchanged these paintings with a bounty on them in the millions in broad daylight in a restaurant parking lot. But in these cases the details are important in determining where the truth lies in these conflicting stories.

There seems to be a heartfelt and determined sense of entitlement that comes across in Elene

Guarente’s own account that may or may not have been justified by the reality

of the cards, or in this case the art, her husband was holding.

“’My

Bobby was sick then,’ she recalled later. ‘He told me he wanted them [the

stolen Gardner paintings] left with someone who’d make sure they were safe and

would be able to provide for me. He thought he could trust Bobby Gentile with

that job. The next year my Bobby died, and I never heard anything about it

after that.’”

The

ailing Bobby Guarente too, might have been less than forthright with his

anxious, soon to be widowed wife, possibly

deluded or delirious, or putting in place a plan to apply pressure on Gentile

into helping out his spouse after he was gone; a dying just trying to get through

the day with a panic stricken spouse.

For

his part, Gentile denies Elene Guarente’s charge that he had the art. “That’s

ridiculous,” Gentile practically spits back when told of the tale Elene

Guarente shared. “I remember that lunch. But not because Guarente handed off

any paintings to me. That’s crazy. He didn’t. What I remember most was that

Elene ordered the twin lobsters. Two of them! And we were only having lunch!”

[page 146]

The oft reported story

of Elene Guarente’s lobster special lunch, even made it into the same episode,

of Last Seen, as told by Gentile's lawyer, Ryan McGuigan. The story

though, she did not deny it, puts her in the light of someone who could be

thought of as grasping and self-centered.

According to Kurkjian in

Master Thieves, “Amore advanced Mrs. Guarente $1,000 from the museum to have

her car fixed, the reason she’d decided to contact them about what she knew.” [page

90]. Anthony Amore strongly denies he ever gave Guarente any money. True or

not, it does suggest a stepping back from her original story and a lack of

sincerity.

4. HORAN: They weren’t planning on spending much time with Elene

Guarente. But something happened after Amore asked if she’d ever heard of the

Gardner Museum.

AMORE: She said, "No." And we’re like, “Well, thank

you, Elene, blah, blah, blah.” But I notice, I notice her hand shaking now. It

starts to shake. And she starts crying. Like, seriously, crying. Not a tear.

She’s crying, like, I have never experienced before. And she breaks down and

says, “I have heard of the museum. My Bobby had those paintings.”

A similar story of a routine interview suddenly

taking a dramatic turning point thanks to a telltale hand tremor, occurs in a

2017 nonfiction book about a different Gardner Heist suspect, Roderick Ramsay, called

“Three Minutes to Doomsday,” [page 18] although for a different crime, that of espionage

in 1988. The anecdote also appears in another book by the same author Joe

Navarro, that come out in 2009, called “What Every BODY is Saying on page 147.”

In this episode of Last Seen Amore say of this

meeting with Guarente thus: “This small woman with short, dark hair opens the

door. She was smoking.”

So too was the subject in “Three Minutes to

Doomsday.” The story of the suspect with the shaking cigarette has been a consistent

feature of Navarro’s public talks since establishing himself as an FBI-trained

body language expert over ten years ago:

“I tell the story in the book what Every BODY

is saying, but also in the new book that comes out in April called Three

Minutes to Doomsday, that whole book is dedicated to this one espionage case,

when I went out to talk to an individual [Roderick Ramsay] who was not a

suspect, who we thought could just provide some background information, on

things that were happening in Germany but when I mentioned the name of Clyde Lee

Conrad, an individual who been arrested by the Germans. This man's cigarette

shook in his hands and when I mentioned that name one more time his cigarette

shook again.

Ramsay

has never been acknowledged publicly as a Gardner Heist suspect, but on August 28, 2014, at 2:45 in the morning,

Last Seen consulting producer Stephen Kurkjian sent an email to ex-FBI

agent, author and body language expert Joe Navarro asking Navarro about

Roderick Ramsay’s possible involvement in the Gardner Museum Heist.

The

similarities of these two stories by two investigators, both at least sharing a

routine interest in one of the individuals, Ramsay, combined with other factual

inconsistencies, the omission of competing narratives, and the fact that the

story was held back until shortly after Elene Guarente was dead, raises doubts about

the investigators’ account as told in Last Seen.

5. HORAN: Elene

Guarente claimed her Bobby had two of the Gardner paintings. When Amore asked

what the paintings looked like, she described an image of a woman sitting down,

seen in profile. In two of the paintings stolen from the Gardner — “The

Concert” by Vermeer and “A Lady and Gentleman in Black” by Rembrandt — there is

a woman sitting, in profile.

In his 2015 book, Guarente told Stephen Kurkjian that in the early 1990s in Madison, Maine, Bobby Guarente had shown her

a painting of a woman sitting in a

rocking chair with her head turned to the side,” like Whistler’s mother. She

later said she told investigators and a grand jury that they didn’t look like

either of the two paintings stolen from the Gardner Museum in which women were

seated in chairs [page 139].

The contention

by investigators that with just a little prompting that Elene Guarente spontaneously

said that she had seen the painting is questionable, doubtful.

As Last

Seen consulting producer Stephen Kurkjian said in 2015: "Even though

they say they've had confirmed sighting, that is not what it appears to be,

that does not mean that an FBI agent or a trained investigator has had proof-of-life

sighting of any piece of the missing [stolen Gardner] artwork.

What that

means is someone whom they believe, some, let's say innocent or not so innocent

third party says 'I've seen it and this is the account I'm giving you,' but

they have no actual proof that they've seen it. It's just that the FBI believes

what they've been told by one person.”

“I know that

person whom they believe did see something and I'm not a hundred percent sure.

I've talked to her. I've talked to people around her, and I'm not so sure that

the trust the FBI and the Museum have put into her is well founded."

—Stephen Kurkjian NewTV interview, October 2015 Time: 26:35

But none of Last

Seen consulting producer Stephen Kurkjian’s doubts made their way into Last

Seen.

6. SHELLEY MURPHY: “Look, when the

FBI says, "We solved it. We know who did it." It's like, "No,

you don't!" Because you don't have the paintings.”

The FBI has never said “We solved it.” They have said over and over

again since 2010 that they define solving it as getting the art back, and not

in the knowing of who did it. Murphy is restating one of the investigator’s

key public relations talking points, but it as a criticism of their messaging.

This statement by Murphy was used by Last Seen Podcast in their podcast trailer.

https://youtu.be/zXPHziXHxNw?t=40

In 2013, FBI Boston's SAIC Richard DesLauriers 2013 stated: “Really,

we’re past the point of the statute of limitations on this case, so we're not

particularly interested in pursuing charges against those who are responsible

for the theft. We're solely focused right now on recovering the paintings.”

Murphy

has been right there the whole time to help make this point clear to the public, writing in 2010 in the Bosotn Globe that: “Law

enforcement authorities who ordinarily vow to catch and punish wrongdoers have

adopted the unusual position of trying to woo anyone who knows where the

artwork is stashed, with promises of immunity and riches.”

False Facts in Last Seen Podcast Episode 6

1. HORAN: “About six months into Operation

Masterpiece, something else happened that would mark a low point in Bob

Wittman’s FBI career. It’s something he and his colleagues are still reluctant

to talk about. It’s almost mundane, except that it’s the office equivalent of a

back stab. The knife in Wittman’s back was a memo. It was written by the Boston

supervisor and sent to FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C. It also went to

Wittman’s old boss, Eric Ives."

RODOLICO: “So you're saying that the Boston

office claimed to the D.C. office that you, Bob Wittman, were trying to get $5

million — the $5 million from the Gardner Museum. What did you think?"

WITTMAN: “It was disgusting and

frustrating."

Wittman's response does not answer the question. Was that or was that not what he was saying, that he Boston office claimed, that the D.C. office said he trying to get $5 million reward? That claim would completely contradict what he wrote in his book. "Priceless: How I Went Undercover to Rescue the World's Stolen Treasures:"

“About

a week after our heated call, Fred [pseudonym of the Boston supervisor] penned

an outrageously slanted EC, one that not only presented a lopsided version of

the way Operation Masterpiece had unfolded but raised questions about my

integrity. The most damning section included a claim by a French

participant that I planned to delay the Gardner sting until after my

retirement in 2008, so that I could claim the $5 million museum reward for

myself. It was a preposterous allegation. FBI agents aren’t eligible for

rewards for cases they’ve worked, even after they retire. Everyone knows

that.” [Page 290].

So, it was not the FBI supervisor in Boston, who didn’t “know that,” and who

accused Wittman of wanting the reward. it was a French participant, who accused

Wittman of trying to delay the return until after he retired so he could

collect the ward.

2. HORAN: “After 16 years,

there was at last a plan in place to recover the stolen Gardner art. At least

some of it. But then, Wittman says, the Boston supervisor canceled it, citing

vague security reasons.”

In Wittman’s book it was a specific

security reasons: "We’re hearing that Sunny [one of the targets of the FBI

sting] thinks you’re a cop. So this changes everything, Wittman. We’re gonna

have to ease you out of this—insert one of my guys or the French UC.” —“Priceless”

page 287 The “vague security reasons” were that his cover was blown.

3.

HORAN: “He’s essentially accusing the Boston FBI of misconduct.”

Wittman’s book makes it quite clear

that it was not simply an issue with the Boston office, or the supervisor from that

office. Authorities in France, where the actual exchange for the art was to take

place, also were opposed to Wittman’s continued involvement.

In his book Wittman wrote: “ “When I

mentioned that it would be delayed for three weeks because Laurenz was going on

vacation in Hawaii, Pierre [Tabel, chief of the national art crime squad.] burst

out laughing.

“What’s so damn funny?” I asked.

“My guys in Paris, your guys in Paris, Fred

in Boston, Laurenz off sunning himself at the beach when you want to do a deal,

losing your friend Eric [Ives transferred to Hawaii (page 293)] from Washington,” he said. “Everyone is giving you the banana

to slip on.”

So not only the Boston office but “everyone,” the Chief of the National Crime Squad in France observed, according to

Wittman’s own book on page 294. What Wittman describes in his book is not "misconduct," but a personally very disappointing change in direction.

False Facts in Last Seen Podcast Episode 7

1. CONNOR: “Bobby was a

typical, Italian crook.”

Nobody is a typical Italian crook.

2. “I wouldn't call him a mobster because mobsters are what you associate

with organized crime. He wasn't that kind of a crook.”

Bobby Donati was that kind of

crook: ““Revere

police Detective Lt. William Gannon said that the body of Robert A. Donati, 50,

of Revere, was found in his Cadillac on Savage Street in Revere by an officer

on routine patrol about 1:25 a.m. Donati was a reputed associate of Vincent

Ferrara, who is awaiting trial in Boston on federal racketeering charges. Donati,

meanwhile, was said to be making collections from bookmakers and loansharks on

Ferrara's behalf. Originally from East Boston, Donati had a lengthy criminal

record involving arson, armed robberies and the theft of securities from the

Boston Stock Exchange. Source Boston Globe September 25, 1991.

3. RODOCLICO: “Myles

Connor was a rock star. His band was called Myles Connor & The Wild Ones. He

headlined clubs around Boston, and opened for big names, like Roy Orbison and

Chuck Berry.”

Myles Connor was not a rock star. He played in

clubs around Boston but never in Boston, or Cambridge. The only documentation

of his music career that ever appeared in the Boston Globe was in advertisements

by the Beachcomber for show-dates for Connor and his band on weeknights. There

are no mentions of his opening for bigger acts, real rock stars, like Roy Orbison

and Chuck Berry.

4. HORAN: “Connor was a

Renaissance criminal.

There has not been a “Renaissance criminal” in 400

years. What would a “Renaissance lawyer, or doctor, or Renaissance bus driver

be? Calling Connor Renaissance criminal

is a badly phrased euphemism for a hardened criminal:

“Myles Connor is one of these guys who committed

every type of crime you can imagine. Make a list. Brainstorm on crimes. He can

check off every box. Sold drugs, stole drugs, robbed grocery stores, banks,

homes, armored cars, implicated in the murder of two teenage girls. You name it.

he's done it, a real bad guy. Anthony Amore 11/12/14 Time 45:00

Also a con man and a Gardner heist huckster: “Every

single person who said they could get the paintings back, one of them is Myles

Connor, who's come forward and said it, they're all charlatans and that's

nicest word I can use for them. Hucksters. —Anthony Amore Anthony Amore Weston Library 10/29/13 Time:

1:24

5. HORAN: “And he says

the question of who he [Myles Connor] would and wouldn’t steal from was all

down to a personal code. A kind of thief’s honor system.

There is no such thing as a thief’s honor

system, and that certainly is not reflected in the violent criminal career of Myles

Connor. He is a “Renaissance criminal,” but

one with an “honor system”?

6. HORAN: “It was a crime spree

in the mid-1970s that solidified his reputation as someone who could outfox law

enforcement.

HORAN: “ Myles Connor did four long stretches

in prison totaling over 25 years in five decades. His internal organs were

badly injured when he shot a state trooper and the police fired back hitting

him “several times,” Connor wrote in his book, with his “shoulder taking the

worst of the damage.” Connor was in prison for all but less than three years of

the 70’s.

7. HORAN: “Which, brings

us back to that parking lot in Cape Cod, where Connor was nabbed with the five

stolen Wyeth paintings.”

“Connor was caught with four stolen

Wyeth paintings, not "the five." Three by N.C.

Wyeth, one by Andrew Wyeth and a

reproduction of another Andrew Wyeth painting.”

8. CONNOR: “And he said, ‘We've

got you now, Connors. It'll take a Rembrandt to get you out of this.’ I said, ‘You

know, you're right.’ And so then I set my heart on getting a Rembrandt.”

This is just one of at least three versions of the story Connor has told about what motivated him to steal the Rembrandt at the

MFA.

In “Stealing Rembrandts,” by Amore and Mashberg,

it was only well over a year later, when he was trying to figure out a way to

avoid prison time, that he and a family friend in law enforcement came up with the

idea of stealing a Rembrandt: “

"I said, 'for Chrissakes, John, what will

it take to get me off? A Rembrandt? And Regan told me, 'That just might do it.'"

In his own book Connor swears John Regan said

to him ’Face it Myles, nothing short of a Rembrandt could get you out of this.’ I

swear these are the words he uttered.”

9. HORAN: “On a sleepy

Monday — April 14, 1975 — Connor launched what sounds like a paramilitary

strike on Boston’s MFA. Connor says there were three vehicles with eight armed

men, one with a machine gun.”

“Two

unknown white males armed with 9 mm semi-automatics.” Boston Globe April 15, 1975. Also a Boston Globe review of Connor's book in 2009 by Shelley Murphy said of Connor's MFA Heist: "They pistol-whipped a guard who tried to stop them and escaped out a rear door," and nothing about a machine gun, and advises that: "The book is clearly shaded by Connor's version of the truth." The April 16, 1975 Boston Globe reported that shortly after 12:30 p.m. Monday, one of the robbers held an unarmed guard at gunpoint while another lifted the oil and wood panel off the wall." It is hard to know what was so sleepy about an early afternoon crime in the largest city in New England, four days before a two days visit by President Gerald R. Ford to kick off the county's Bicentennial celebration.

10, CONNOR: “As the exit

was made down the front steps there was a phalanx of guards that came rushing

down.”

Boston Globe reported just two guards responding

to the theft before the thieves left the building.

11. CONNOR: “And there was

a guy with a machine gun, brrrrr. Let the machine gun go off. They went right back.”

There was no machine gun. “As the thieves

fled to a waiting car, the armed man fired three shots, hitting no one but

adding a movie-scene flourish to what was then thought to be the most expensive

art heist in American history.”

12. CONNOR: “The guy would

not let go of the painting. The guy ran up to the back of the van and latched

onto the painting.”

They left the scene “in a black and gold Oldsmobile or Buick” Boston Globe April

14, 1975 afternoon edition.

13. HORAN: Don’t shoot the

guard,” Connor said. One of them smashed him in the head with the butt of a gun.”

"The guard tried to stop the

men as they ran toward the turnstyles inside the entrance and one of

them clubbed him with a pistol butt." Boston Globe April 15, 1975t

The thief who removed the Rembrandt from the Boston MFA was

described by witnesses as a white male, about 20 years of age, 5-foot-9, about 140 pounds, with long blond hair.

Myles Connor,

5-foot-6, was 32 at the time of the theft, and claimed he was wearing a

brown wig and leather chauffeur's cap to cover his red hair,

during the MFA robbery, when he took credit for this violent crime decades later.

Connor better fits the description of the other thief: "White male, 5-foot-6, about 135 pounds, about twnety years of age." This is the suspect police said "

fired two shots at the museum guard."

And if the taller man was the one who took the painting out of the museum then

then it was the shorter crook, possibly Connor,

that clubbed John J. Monkouski 66, of Dorchester, a retired Boston Police, with a pistol butt, who then required "

a number of stitches" for a head wound at Peter Brent Brigham Hospital.

14. HORAN: “There was just one problem,

as Martin Leppo recalls. On March 18, 1990, Connor was serving a long federal

sentence for drug trafficking.

Not true. “After months of allegedly selling

about $500,000 in stolen 17th Century paintings by ''old masters'' and other

antique artifacts to an undercover federal agent, authorities said Myles Connor

Jr. was arrested Wednesday night when he allegedly sold the agent a kilogram of

cocaine. Connor was charged with transporting stolen property and possession of

a controlled substance with intent to deliver.”

Leppo was not Connor’s lawyer for these charges

in Illinois.

The

recollections of an 87 year old confident of Myles Connor, concerning something

that happened 30 years earlier, of which he had no direct involvement, is what

the Boston Globe and WBUR consider being worthy of the term “deep dive” into

this historic case?

15. HORAN: “He [Myles Connor] was in prison in Lompoc,

California.

He was not. According to newspaper accounts and

his own book, Connor was in the Sangamon County

Jail in Springfield, IL awaiting sentencing, not serving a long sentence, according

news stories at the time and his own book. His sentencing was delayed twice

after the Gardner heist. Connor and his cohorts had plenty of opportunity to try and initiate a

deal.

16. LEPPO: “When the Gardner

was hit, Myles became the No. 1 suspect. Did he orchestrate it? And so forth

and so on. So that was number one.

That was not "number one." Connor had been in

jail in Illinois for over a year before the Gardner heist. The FBI didn't even try to talk to Connor: “We've made no

attempts to speak with Myles Connor. FBI Supervisory Agent Edward Quinn. "He has not been requested to meet with the FBI Connor’s defense

attorney Boston Globe 5/13/90. He was not the number one suspect.

17. CONNOR: “How I'm 100

percent sure that they [David Houghton and Bobby Donati] did it was because David Houghton, who was longtime

friend of mine, flew all the way from Logan Airport to California just to tell

me: “‘We've done with. We did it. And we got a bunch of paintings, and we're gonna

use a couple of these paintings to bargain you into a reduced sentence.’"

The Mensa member, Myles Connor, doesn't even

know what state he was in when Houghton supposedly told him he and Robert

Donati robbed the Gardner Museum to get him out of prison.

From Connor's 2009 book, page 285, In the Fall of

1990 I was transferred to federal penitentiary in Lompoc, CA." Also in his

book he says that "several weeks later [of March 1990] I received an unexpected

visitor, David Houghton... "David's visit was the last time I heard from

either man [David Houghton or Robert Donati]." So that means Connor's

visit with Donati was in Illinois. It would have to have been several months

later for him to have been in Lompoc, CA.

18, HORAN: “He settled on

one that was on loan to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Portrait of Elisabeth

van Rijn,” Rembrandt’s sister.

It is not the artist’s sister.

19. The

correct name of the painting is “Portrait of a Girl Wearing a Gold-Trimmed

Cloak,”

A “proposed identification for the sitter is

Rembrandt’s younger sister Elisabeth (Lysbeth). However, Rembrandt executed

this painting in Amsterdam and Lysbeth apparently spent her whole life in

Leiden.”

“The same model appears in two other paintings

that Rembrandt executed in 1632: “A Young Woman in Profile with a Fan in

Stockholm, and Bust of a Young Woman in a Cap in a private collection in

Switzerland…The presence of these four paintings featuring the same model by

Rembrandt, and his workshop makes it highly unlikely that Young Girl in a Gold-Trimmed

Cloak was a commissioned portrait. Interestingly, the same model, in a nearly

identical costume, appears in two of Rembrandt’s history paintings from the

early 1630s: “as Europa in The Rape of Europa, in the J. Paul Getty Museum, and

as the woman (Esther?) in the Old Testament scene in Ottawa.

“Portrait

of a Girl,” once believed to be a rendering of Rembrandt’s sister, inspired the

facial types of many of Rembrandt’s heroines in the early 1630s.

False Facts in Last Seen Podcast Episode 8

1. HORAN: “At 5:30 in the morning on Christmas Eve, 1980, Fred Fisher, then the 40-year-old director of the Hyde Collection in Glens Falls, New York, awoke to a telephone call from police. Someone had tried to rob the museum.

The robbery attempt was on December 22, 1980, so the phone call would have been on December 23rd, not Christmas eve.

The Post-Star December 26, 1980:

A van driven by Mary ------- W------, 26, of Watervliet, arrived late Monday [December 22, 1980] When the driver left the van to pick up the package, she was allegedly confronted by a man with a gun who forced her back into the van and made her drive to Oakland Avenue in Glens Falls, which runs parallel to Warren Street and behind the Hyde Collection. So it was December 23, not “Christmas Eve.”

http://gardnerheist.com/Hyde_Robbery_12_26_1980.pdf

2. HORAN: “When he was arrested in Glens Falls, McDevitt explained his alias to police by saying “I was doing this to avoid trouble with Massachusetts authorities regarding a particular legal affair.” That’s con man code for felony.”

That’s not any kind of code, con man or otherwise. McDevitt was saying his alias was defensive in nature, intended to avoid the authorities and consequences of his past actions, not as part of a plant to commit more crime.

3. HORAN: “An article in The New York Times outed him [McDevitt] as a prime suspect in the Gardner heist.”

The New York Times said he was an intriguing suspect, not a prime suspect. And he wasn’t outed, he came out:

“William J. McMullin, a spokesman for the F.B.I.'s Boston division, would neither confirm nor deny the identity of the suspect. But Brian M. McDevitt, a screenwriter who moved from Massachusetts to California about two years ago, acknowledged that he had submitted to F.B.I. questioning in his lawyer's office in Boston about the robbery…McDevitt garrulously discussed the case by telephone” for the story.”

When McDevitt was on Sixty Minutes sixth months later, Morley Safer observed "you do get the distinct feeling that he [Brian McDevitt] wants you to believe he did steal the [Gardner Museum] paintings."

4. HORAN: “Brian McDevitt served two years for kidnapping and attempted robbery.”

“McDevitt, who was 20 at the time, served a few months in jail for the attempted robbery.” —Boston Globe 3/18/17

Convicted of unlawful imprisonment and attempted grand larceny, they [McDevitt and Michael Morey spent less than a year in jail. “Loot: “Inside the World of Stolen Art” by former FBI Art Crime investigator Thomas McShane

5. RODOLICO: “Former FBI Special Agent Thomas McShane was also in Boston on March 18, 1990. He’d been among the first on the scene of the robbery at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.”

McShane was also NOT in Boston on March 18, 1990

"I was summoned to Boston on the Monday after the weekend robbery." From McShane’s book “Loot” page 307

6. HORAN: “His fingerprints would be among the first to be sent to FBI headquarters in the wake of the Gardner Museum robbery.”

Mr. McDevitt said he had been questioned for an afternoon and had allowed himself to be photographed and palm-, hand- and fingerprinted. So it was over a year and a half before anyone’s fingerprints were sent to FBI headquarter in the “wake” of the Gardner Museum robbery. Eighteen plus months is not “in the wake” of the robbery.

7. MCSHANE: “Brian Michael McDevitt. He was interviewed by the FBI and immediately afterwards he took off to California. This is a con man of a nature of Bernie Madoff.”

Media coverage would seem to contradict this claim that McDevitt was interviewed by the FBI before he took off for California in around June of 1990. Part of McDevitt’s attention-getting campaign for his status as a Gardner Heist suspect, was his talking about the extent to which he was being investigated by the FBI.

If the interview with the FBI in 1992 was the second interview and his second refusal to take a lie detector test, he would have said so. If they had met with him in 1990 to the extent that he refused to take a lie detector test, which McShane wrote in his book, then why did they wait until 1992 to fingerprint him?

Here is a report that suggests that a suspect fitting McDevitt’s description was being scrutinized, but not interviewed from page 1 of the May 14, 1990 Boston Globe: Suspects' movement are under close scrutiny by federal agents, including one suspect who was under surveillance during a recent arrival at Logan Airport. Investigators are looking at some suspects because methods they have employed by previous robberies closely resemble those used in the March 18 theft. This would certainly describe McDevitt who lived at

Two stories, one in the Boston Globe and one in the New York Times seemed to suggest that this interview of McDevitt by the police was something new for him:

“Speaking by telephone from Los Angeles, Mr. McDevitt said he had been questioned for an afternoon and had allowed himself to be photographed and palm-, hand- and fingerprinted,” in around Autumn of 1991.”

There was a day last autumn [1991] when Brian McDevitt siting in the office of his small loft house in Hollywood Hills, proposed writing a screenplay about a brazen art theft during which thieves hid the stolen treasures deep in a German cave. Just a few weeks later, McDevitt found himself at the center of an investigation into the largest art theft in history, when the FBI summoned him back to his lawyer's Salem office and asked him what he knew about $200 million in paintings missing from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Boston Globe 6/2/92

In his Sixty Minutes interview, McDevitt seemed intent on maximize the extent he was being watched and suspected by the FBI, so it would have been in his interest to mention he had been interviewed in 1990 if that were the case.

False Facts in Last Seen Podcast Episode 9

1. RODOLICO: “This now

vacant lot was once a rented, warm weather getaway for a Boston gangster who

tops the list of Gardner suspects.”

Whose list of Gardner suspects does Guarente,

dead 14 years in 2018, top? The only thing connecting Guarente to this property

is his name on some government forms, and the story about which government forms

those are has changed. There is no way of knowing what the function of the house

or the address was. His wife said she did not know anything about it.

2. LUISI: “And they were

talking about the artwork. And he says, "I know where the art's buried."

He said it's in Florida under a concrete floor.”

Originally Luisi said it was buried in a cellar

in Florida. But then, there are no cellars in Florida.

At the time of the initial story, in 2016,

Luisi was promoting a website and a self-published book about his transformation

from Mafia capo to Christian evangelist. After his 1999 arrest on drug

charges, Luisi agreed to cooperate against mobsters from Boston to Philadelphia.

Why didn’t he bring up what Guarente allegedly said to him then? Why would

agents wait until 2012, to ask Luisi about Guarente when they had suspicions

about Guarente going back to 2010?

3. RODOLICO: “Steve knew Guarente had lived

in Boston and Maine. But buried in his paperwork on him, he found a DEA report

with an address he’d never previously noticed.”

In his Boston Globe story about this in 2016, Kurkjian reported Maine

State Police records indicate that Guarente listed a lakeside home in Orlando

as his residence for several years in the early 1990s,” and there was no mention

of a DEA report. In the Boston Globe story, Kurkjian reported that The FBI has searched

Guarente’s property in Maine, and Gentile’s property in Connecticut, repeatedly.

Kurkjian was aware of a property that should be of interest to the FBI based on a

federal DEA document, that the FBI did not know about? Maybe they just did not take

an interest in it?

4. RODOLICO; “The lawn

rolled down to a white sand beach. Ferrari didn't remember Guarente, who'd rented

the house in the early '90s.”

The fact that a professional drug dealer had an out of state address

attributed to him on some government forms is not proof that he personally rented

the property.

Guarente’s widow, Elene, said she was unaware of any Florida

property connected to her husband, “but he was always traveling one place or

another without telling me where he was going.”

5. HORAN: “There was just one problem. This

lead wasn’t about just any anomaly buried underground. It was about the Gardner

art, which made this Orlando lot potentially a crime scene.”

A septic tank, which, Last Seen Podcast's "big dig" uncovered

is not an anomaly on a residential lot in Orlando.

One

of the more commonplace functions for Ground Penetrating radar systems is

locating Septic tanks. “Trained professionals can easily check the scanned

results and let you know what is located under that concrete slab rebar.”

If there was any chance was going to be found at this location, the FBI's Geoff Kelly and Anthony Amore, who had both been officially involved in the investigation for well over ten years would have been there.

Conclusion

Community facts are community property. In an open society, the public relies on news sources such as the Boston Globe and WBUR, an NPR affiliate, to disseminate, and preserve the facts of shared community interest and importance.

However, last year’s Last Seen, the award-winning podcast by WBUR and the Boston Globe, about the 1990 Gardner Museum heist, performs the opposite of that most essential mission of journalism, that of informing. Instead, Last Seen consistently misinforms the public, to such an extent that it is not an overstatement to say that misinforming is a principal characteristic of Last Seen podcast.

The ten podcast episodes ran weekly from September 16 through November 19 of 2018. Since then, little to nothing has been done to extend interest in the podcast beyond accepting, a couple of podcasting awards, with something approximating a bare minimum of acknowledgement.

Nonetheless, Last Seen lives on, not only as a podcast, but also through the podcast transcripts, which are hosted by both WBUR and the Boston Globe websites.

These transcripts and other online Last Seen materials, are thoroughly “spidered” by google and Bing, and highly ranked on these major search engines, as are the companion articles, videos and related media.

This Last Seen online juggernaut has made itself a top tier stop of initial or casual research on almost any specific topic related to the history of this epic travesty. While the sheer scope of the production with its emphasis on delivering mass market entertainment value, is sure to captivate many, it falls far short of accurately informing any who encounter Last Seen podcast and related content. Transcripts of the ten Season One are part of the permanent electronic archive of the Boston Globe daily newspaper.

This Gardner Heist media juggernaut has surpassed and sidelined even more significant past coverage of the Gardner heist by WBUR itself. When in 2013, the Garner Museum did an exhibit related to historic crime by Sophie Calle, also called “Last Seen.” In this WBUR news story about the exhibit, Gardner Museum director Anne Hawley was quoted recalling:

"The museum was experiencing these bomb threats coming from people in penitentiaries that were trying to negotiate with the FBI on information they said they had — and the FBI wasn’t responding to them, so they were hitting us."

This blockbuster disclosure has gone ignored by the local media and by Last Seen podcast, although Hawley repeated the claim in a subsequent interview with Emily Rooney on WGBH in December of 2013. It surpasses anything newsworthy in terms of our understanding of the Gardner Heist or the ensuing investigation from this 2018 Last Seen Podcast.

While the Gardner heist remains an open case, Last Seen is really a podcast about history, about a single specific, sad but spectacular event from 1990, as well as the investigation into who did it and the efforts to get the art back since And although it was produced by two generally reliable media sources, the Boston Globe and WBUR, and is a podcast about history, it is not a history podcast. Significantly there were no historians involved in its production.

It would be a difficult to find a historian who has or would be willing to endorse this highly promoted, high profile podcast. The production is replete with false information. Last Seen effectively pollutes the community data stream, in passing along fallacies and bolstering false narratives about the Gardner Museum heist and its investigation. Inaccuracies in Last Seen now adulterate the facts everywhere from google, to google news and outward to the Gardner Heist Wikipedia page, to high school research projects on the case.

Mrs. Clark's APUSH Class 2019 (A Block).

Gardner Heist Documentary

The false narratives found in Last Seen, though not originating with the podcast, include a false narrative suggesting that in the days, weeks, and years following the Gardner heist, there was a standard kind of investigation by the FBI, an investigation comparable for example with the investigation of the Worcester Art Museum robbery in 1972, and the Lufthansa heist at LaGuardia Airport in 1978, as well countless other FBI investigated crimes found in books, television programs, and films.

The Gardner heist investigation, Last Seen Podcast asserts, sought not only to recover the stolen art in the early years, which they did, but that they also sought to figure out who was responsible for the thefts, and bring them to justice. But this whodunnit aspect was never a part of this FBI investigation.

Last Seen Podcast misleads the public and listeners to the podcast on this facet of the FBI’s exclusive (by fiat) response to the case in two ways: “First, by inserting events into the historical record in 1990, that did not occur at that time, and also by placing considerably more doubt about the possible involvement of security guard Rick Abath, than the evidence known from the very first day of the investigation logically justifies

Another false narrative of Last Seen, one which did originate with the podcast, is that the FBI conducted a similar kind of standard investigation, to identify the visitor in the Gardner heist eve surveillance video, which the U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts, Carmen Ortiz, released to the public on August of 2015.

After years of investigation the FBI concluded, according to Last Seen, that the individual in the video was, after all, none other than the Gardner Museum’s very own Deputy director of security: “Three former security guards we interviewed confirmed his identity, as well as a source close to the investigation.” —Last Seen Episode Two

The director of security at that time, retired Army Lt. Colonel Lawrence O’Brien, died after investigators began taking a renewed interest in the surveillance tape, but before an excerpt was released to the public.

Additionally, an extreme makeover for Myles Connor, by Last Seen transforms this career criminal from con artist, “huckster,” to credible source, as well as from cold-blooded cop shooter, into a kind of rock ‘n roll / art thief folk legend; another false narrative and a particularly odious one of Last Seen Podcast

Connor spent over 80 percent of his time in the quarter century prior to the Gardner heist and all of the decade following it, serving long sentences for four separate arrests and convictions.

Finally, despite the FBI’s acknowledgement that they know who the thieves are, Last Seen serves up a rapidly rotating carousel of possible Gardner Museum robbers. The names of these mostly mutually exclusive “suspects” serve as virtual sentries on the front lines, of protecting the highly classified identities of the actual thieves. And Last Seen podcast’s roster of possible perps is not even a complete list, according to Kelly Horan, the senior producer and a senior reporter of Last Seen said, in the podcast’s final episode: “

“The only thing more cluttered than our brains is the cutting room floor. There are characters and storylines and theories that are so compelling, we just couldn't fit them all in,” Horan said, kicking off Episode 10.

Last Seen does not challenge, disprove or endorse any particular theory. What it does do is flood out the question of who the thieves were, with so many competing possibilities, that nothing makes sense. Serious research into the topic leaves the mind “cluttered.” More information renders less meaning. Meaning is unattainable in the case of the Gardner Heist, at least that was the experienced of the investigative journalists at WBUR and the Boston Globe.

Are we to be a society of crowd sourcing, where those in authority use information technology to engage with and derive quality feedback from the communities they serve? Or one of crowd saucing, where this technology is used to manufacture consent by rulers, who presume to know better, without community input.

When it comes to the Gardner Heist investigation it would appear to be the latter.

Less than a month after the release of Last Seen’s final episode, Anthony Amore was interviewed on a podcast called “The Horse Race” by Steve Koczela, who is head pollster of WBUR. Koczela to Amore said in the interview: "I've read the book, I've read several books, everyone is listening to the podcast now, will the Gardner paintings ever be found?" And Amore finished his reply with: “Don't believe the books. Don't believe what you read in them. Suspend disbelief and know that people are working really hard behind the scenes."

Four of the authors of “the books,” Robert Wittman, Ulrich Boser, Thomas McShane, and Stephen Kurkjian, as well as Amore, co-author of “Stealing Rembrandts” were all involved in the making of Last Seen. Kurkjian was the podcast’s consulting producer.

Flooding the information space with multiple scenarios, and suspects based on weak, nonexistent, and misused evidence, and factually incorrect information requires a conduit, and Last Seen podcast delivers, blasting away into the community property of facts, with deliverables of fallacies, and false narratives, for an icing avalanche on the cake, of a campaign of misinformation, which began in early 2015, led by the Boston Globe.

Can we afford to only push back when it is personally inconvenient or offends our own sensibilities, or does each incursion demand pushback? Does each instance not embolden those in power, and those who seek it, to employ these dark arts of mass communication again and again?

When an investigator speaking about the Gardner Heist says: Eyewitness accounts are really unreliable. It's quite common that they give descriptions, but the descriptions are usually inaccurate,” as Amore has done, how long before someone applies that false information in a jury box or some other legal proceeding?

The misinformation is supplied for a specific context, but if it is believed, then it has the potential for being applied in other less suitable situations as well. This may make work in countries running on their oil and mineral wealth, as is the case with Saudi Arabia and Russia. But a knowledge-based economy, like the United States, depends on the free flow of ideas and a smooth flow of accurate information .

This report is not an emotionally pitched laundry list of the arguably specious. This is a report about matters presented as fact in the podcast Last Seen podcast by WBUR and the Boston Globe that are demonstrably false: Names wrong, people wrong, times wrong, dates wrong, places wrong, titles wrong, actions wrong, and descriptions wrong, a tip suggesting an iceberg.

Kerry

Joyce

Copyright

2021